by Francis Commercon, Menglun Township, Yunnan, China

The scar a wild boar left on his cheek wrinkles into a smile as he recalls the Red Junglefowl and other wildlife he shot forty years ago at this natural spring deep in the mountainous tropical forest of Xishuangbanna, southwest China. He talks fondly of the muntjacs who will come to eat the “Yugan” fruits and the palm civet whose muddy feet left their prints up a nearby tree. I peer through my binoculars at the bird ponds we just finished building together. The ancient liana on which I sit was my friend’s perch so many years ago as he aimed at his quarry. Over my interactions with the local ethnic people of this region (primarily the Dai and the Akha), I have remarked time and time again that their appreciation for wildlife is no less than my own—and indeed it is oftentimes rooted in a much deeper connection to the forest than I could ever have. The Akha friends leading me through the forest today are eager to help me and my research institute, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens (XTBG), build community-based ecotourism to promote biodiversity conservation in his village. But it is clear they see the animals of this forest fundamentally differently than me or the ecologists and educators at XTBG. They reminisce over muntjac meat eaten long ago, and they ask if I have ever tried it. And this is where I feel the complex dilemma that follows me throughout my fieldwork.

I feel stuck between an anthropologist’s desire to integrate into the ways of his host community to understand them more deeply, and a conservationist’s very real concern that overhunting is irreparably damaging the forest ecosystem. I cannot voice strong opinion against the hunting and consumption of wild meat without destroying my connections to those informants who would teach me the most about their community’s hunting. I know my calls against eating wildlife, if coming from the outside, will never cause behavioral change. I know conservation behavior will only come from within the community; it will only spread through existing systems of social influence. That is why I want to get into the “inside” and understand people’s psychology and the social influences behind behavior. So, I feel confused between my biodiversity conservation goals, which involve attempts to change the community based on ideals from the “outside,” and my dream of being a good anthropologist, objectively studying his host community from the inside. I often wish I had not specialized on studying illegal wildlife hunting; I would have been allowed deeper into my study communities if I had instead delved into non-illegal aspects of traditional culture. And I often wish that I did not have the personal agenda of publishing my results for the western world to see, because attempting to tell this story according to the statistical version of truth steered me away from reliance on ethnography, which would have been more socially sensitive. As I will describe below, I spent the last few months collecting large quantities of anonymous survey responses to uncover correlations between hunting behavior and various levels of norms and peer influence in Dai and Akha villages around Menglun Township. I was too preoccupied with an ecologist’s desire for replication and statistical significance to accord adequate attention to the more spontaneous and unstructured collection of ethnographic data. But I know ethnography would be much more useful for understanding the psychology of topics like illegal hunting. Looking back, I have many ideas about how I can improve my approach as I move forward as an international conservation social scientist and as a conservation practitioner.

Being in the forest with my Akha friends over the past several days has felt like a healthy rectification of my previous approaches. Unlike with the Dai, whose forest belongs to the strictly regulated Nature Reserve, with the Akha I can trek through their forests—which are outside the Nature Reserve—without worrying about being caught by the police and without my friends worrying about accidentally doing something illegal. I can observe their local knowledge and connection to the plants and animals as they guide me along the bamboo lined ridges and banana-filled stream gullies of their ancestors. They tell me how and where to see the wild boar whose tracks we frequently encounter. They can detect where a Silver Pheasant recently foraged simply through a cursory scan of the leaf litter. They know which vine will yield drinkable water when you are thirsty, and they see the walls of green vegetation around us like a pharmacopeia of medicines. With them, my journey through the landscape is full of fascinating tastes, smells, and stories. Valuation of nature in my conservation-oriented social circles tends toward non-consumptive observation and protection. I am always worried about the human impacts on nature as being unsustainable. But the Akha people are a major component of their forest ecosystem, using innumerable forest products and, through that use, affecting the forest in turn. They seem to have never worried about their harvests being unsustainable, perhaps because throughout their history the forest was always vast and its resources were always abundant. I think most people in my study communities do not grasp the underlying principles of the modern conservation narrative that nature is a fragile thing to be “protected” from depletion and destruction by humans; this is still a fairly foreign concept that has not proved relevant until the past two decades. People here were still wanting for food in the 90s. The forest is, for them, first and foremost a resource to be used. As I hike through the forest with my Akha friends, I try to see the environment through their eyes. I know they love the forest just as much as I do, but their understanding of people’s relationship to it is vastly different from mine. I think understanding and respecting this difference in understandings between local people and conservationists is likely the greatest challenge in developing community-based conservation programs.

My fieldwork in the Akha people’s community forests over the past several days is part of an effort to survey birds and wildlife to determine optimal locations for bird ponds. We are trying to establish locations to attract birds with water and regular provisioning of meal worms (i.e. “bird ponds”) so bird photographers will pay to come take pictures of birds. The income is intended to generate economic incentives that would discourage the rampant harvest of wild birds from these community and state-owned forests. One day while setting up camera traps, we heard five gunshots in one hour from the nearby hillside.

I recently visited an Akha village in the Mengsong region of Xishuangbanna that has seen some progress in encouraging bird conservation through similar bird pond ecotourism development. Huilashan Village has five privately-owned bird ponds, of which a portion of the proceeds go toward village projects. Although this small group of pioneering villagers has yet to break even on their investment in bird ponds (they have personally funded all expenses), the influx of birders brought in by their efforts has led to new community norms about protecting and appreciating birds in non-consumptive ways. The tourists also bring in income to a community-owned local restaurant and by purchasing the villagers’ tea (which may bring in more income than the birdwatching itself). But my discussions with the assistant village leader made me suspect that some form of social influence was responsible for behavioral change disproportionate to the economic benefits of the project. He even described how his community patrols, catches, and fines people unsustainably fishing or otherwise unlawfully exploiting forest resources. I’ll note that such community-based protection of natural resources—and the construction of the bird ponds themselves—is only possible because the land is not part of the nature reserve.

I am currently leading planning of a two-day trip to take our project participants to Huilashan Village so they can learn from the experience of villagers who have already endeavored in birding ecotourism for two years.

Another critical challenge for community-based conservation is the discrepancy between local and western scientific versions of knowledge and reality. Specifically, I have seen local ecological knowledge (LEK) clash with western scientific ecological knowledge (WSEK) when the camera traps we deployed failed to corroborate villagers’ assertions that their chosen bird pond sites had many specific species of wildlife. In a recent meeting, I realized other project leaders were convinced that the villagers were exaggerating and that hunting pressure had left their forests devoid of interesting animals. I found myself defending the villagers’ strong conviction that there might still be animals, that the cameras had not functioned properly or had not been left for long enough–but the villagers’ anecdotal evidence is often unpersuasive for those educated in scientific thought.

Now I am designing a new camera trapping survey using improved knowledge of the method to re-examine the wildlife coming to the bird ponds, and I am particularly focusing on surveying for Blue-naped and Hooded Pittas, which would be of particular value for attracting Chinese tourists. I am letting local villagers lead me to places where they feel Pittas can be reliably seen. In the process I have improved both my understanding of LEK (villagers’ vast knowledge of what birds can be seen where and at what times of year) as well as WSEK (camera trapping techniques).

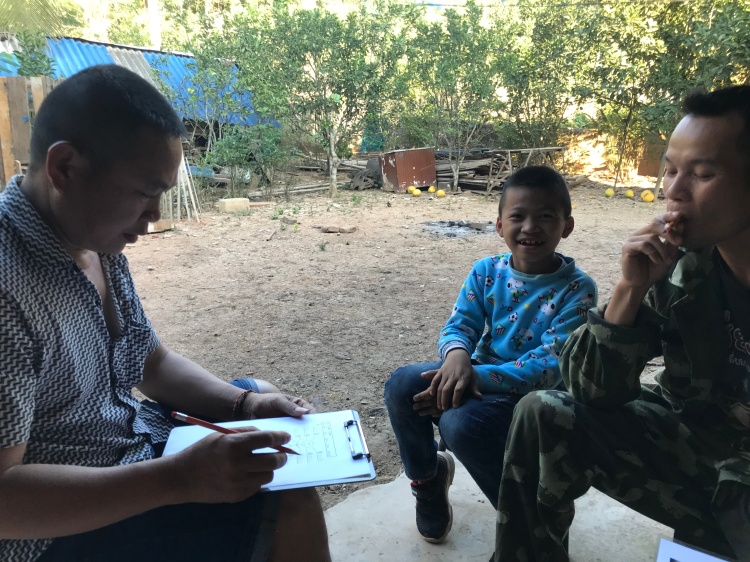

In my last few weeks in China, I would like to finish my involvement with the bird pond ecotourism work through focus-group discussions in each village regarding the results of my hunting surveys. In five villages (and soon a sixth), I collected 139 anonymous responses to a 50 question survey using Likert-type scales to quantify people’s perceptions of social norms, law enforcement effectiveness, and moral obligations and to statistically correlate these with hunting behavior and intentions. I feel that such discussion would yield invaluable insight for interpreting the results. I will combine these discussions with discussion of the birds I have recorded during my forays into their forest. I will teach them the Chinese names and some educational facts about them, and I will record notes on their local knowledge of each species.

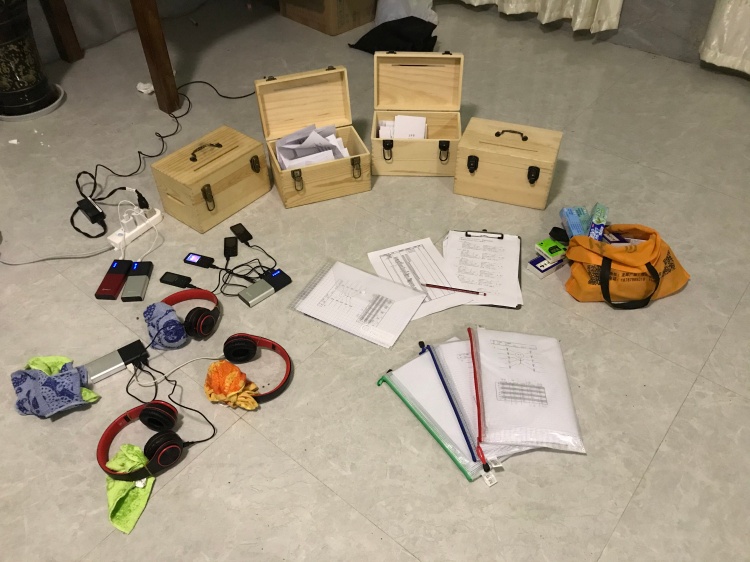

And I will also finish the editing and proofing of my dataset for my Fulbright research, which is a separate research project from the community-based ecotourism outlined above. Over the past few months, I used 130 pilot survey responses from five pilot villages to develop a 30 question survey investigating how peer influence and social networks shape wild meat consumption in Dai communities. I proceeded to collect responses from 360 people in my host village by coordinating a team of four local assistants. I still have to comb through the data to edit mistakes, but at least all my data is entered into my computer. Then I have to prepare for the long job of turning my data into results and then writing a paper. I feel truly hopeful that I may have uncovered some interesting findings for both the sociology and human dimensions of conservation literature, and I feel giddy with the excitement of scientific discovery!

Below, I have added several pictures to tell the stories of many interesting moments for which the above paragraphs had no space. There was a time I wished for everything I did and saw to be noticed and recognized by others. I saw my life as a struggle to construct a persona which, when squeezed into a college or scholarship application, would propel me forward professionally. Now I start to question what “forward” really means, and I begin to doubt whether I care that anybody but myself knows what I’m doing with my days. I applied for graduate school and also for a major nationally-competitive scholarship in the past couple months, and despite incredible effort on each application, I realized that constant aspiration for professional advancement may simply leave me unfulfilled. I want to live my life so that if I die tomorrow I will be happy with what I did today.